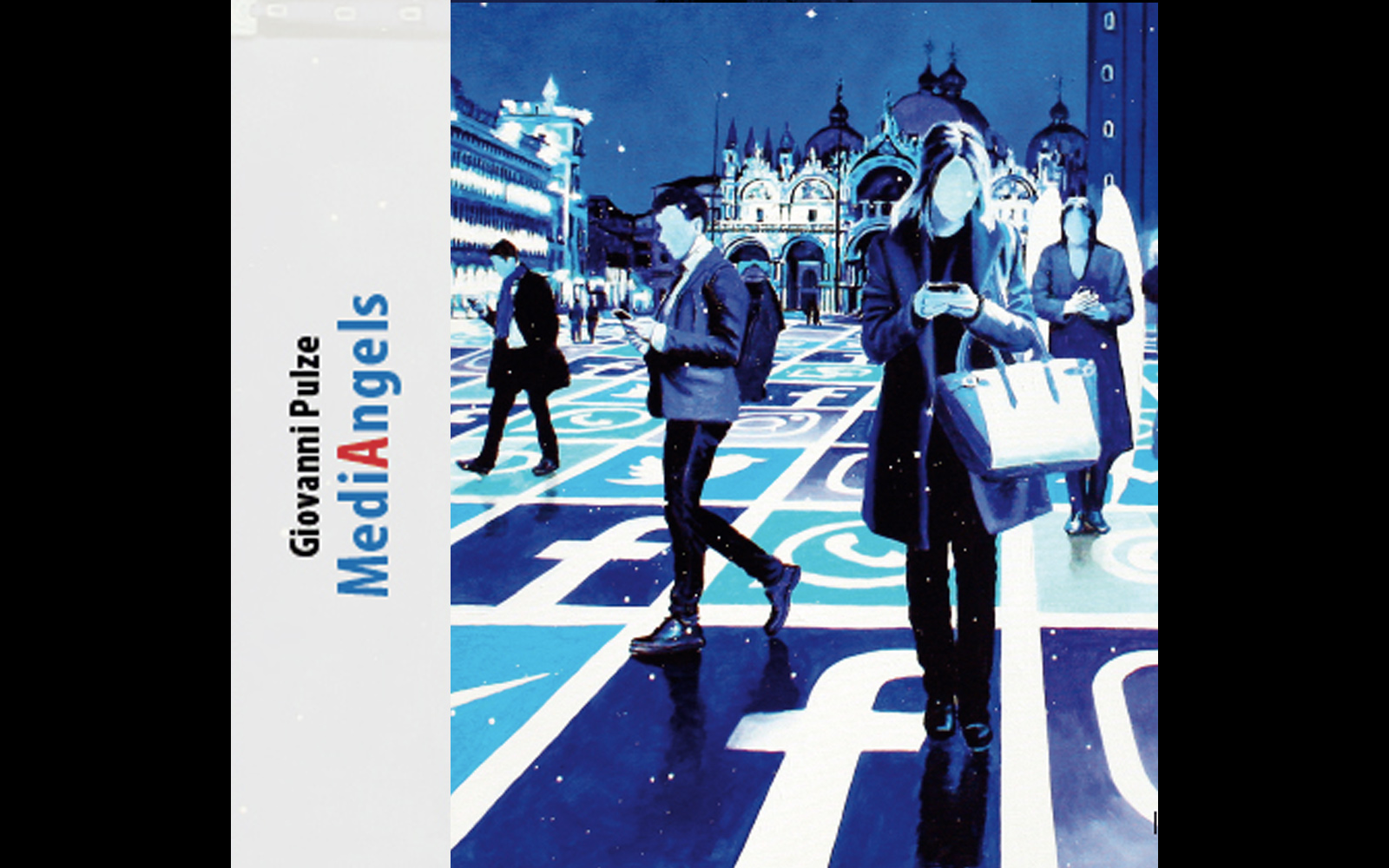

BOOKS / 2019 MediaAngels

Mediangels by Gabriele Perretta

Those who are accustomed to seeing Giovanni Pulze as a painter with a brushstroke as quick as the flash of a blade, refined and elegant even in his depiction of the urban landscape, and those who think of Pulze as a New Yorker will probably be surprised by his new cycle on Angels and the rise of the smartphone.

But if we bear in mind the painter's early training, his experience of the media and his open and avowed love of the meta-photographic image, we will come to understand how these panels on messengers represent a new metamorphosis for this neo- or cross-media artist. It is easy to be surprised by the “hyper-actual” atmosphere, found in the works of the most provocative interpreters of “post-pop”, “narrative art” and above all the so-called “simulationists’”: this is precisely the mood dear to Giovanni Pulze, inspired by a human sentiment suffused with urbanity and collectivism, attentive to the facts of everyday communicative life, and seeking not to surprise with frills and effects, but rather to grasp the innermost and most subtle elements.

Giovanni Pulze began his journey as a painter in the last two decades of the twentieth century, at a time when Expressionism was extricating itself from the artistic and social life of Italy, the most pernicious and abstruse aspects of Symbolism and Abstractionism were prevailing, and the perilous mawkishness of a Decadent movement was undermining and demeaning the original and vital vision of the conceptual.

Giovanni Pulze did not write Metropolis or the post-Metropolis works of G. Simmel, but rather sees the Metropolis in the exhaustion of a vision whilst not going beyond it. His painting comes to an end as the vision of the metropolitan image is exhausted whilst remaining under his control. G. P. does indeed paint “what he sees”, but does not deny the evidence of what he sees. If he had turned away from homage to iconicism, he would instead have painted without seeing. As an abstraction. Therefore his experience remains a medial one : medial, the collection of iconographic formulae, the binding of reality.

This is still - despite the fact that his intellect puts him on the threshold of the contemporary agora - the cover of cross-media. Despite the particular reality in which he finds himself, Giovanni still considers painting in terms of the plural and not as a singularity, which is independent of the whole and does not need to be unified. And it still speaks of a universal form just when it is at the height of the deceptiveness of the image. But how to express the very deceptiveness of images, without positing at least one image that does not deceive? That is, without submitting to the principle of the ineffable photograph? The simulation ends here and its virtue is precisely that it does not decide, that it leaves something unresolved without becoming an obsession.

Pulze proposes something which remains pictorial but in terms of a vision and not a response. The nexus of which Pulze speaks - like the nexus of the metropolitan communicative topology of the media - is still part of a hybrid conception of the image and therefore a pluralistic conception of the media messenger. The same idea that photography shows in the formation of the so-called artificial mash-ups of Photoshop, or of apps that manipulate the image.

In Pulze's new cycle, Mediangels, I think I detect a hypothesis that is quite insidious in terms of the consequences it implies: there is no topology of the image and the object. The object of media painting is non-topological. Pulze pushes towards the universalisation of vision and an abandonment of individuality in the name of the ineffable. Metropolitan topology proposes the absolutism of vision in the elimination of individuality. What is this banal regularity - made up of forms that are always imaginative if continuously unformed - if not a kind of idealistic metageometry? Such a form is nothing more than the geometric representation of the universal Platonic idea and how it can pervade an infinite number of individual ideas, without changing its essence. A sort of sign of the sign, or, if you prefer, a ghost of the ghost. It is the very structure of what Pulze calls an icon messenger, i.e. a meta-messenger. The continuity hypothesis, however, is an avoidance of time: the crowd is everywhere, in the supermarket, in the bank, in the hospital, in the classroom, on holiday; everywhere and at all times, in summer and winter the crowd assaults the image, surrounds it, covers it. It is always there.

There are fewer and fewer places where there are no crowds with their smartphones, texting away and lost in a hyperreality; fewer places where you are not assaulted by the pictorial renditions of Mediangels. Yet man suffers from loneliness, an anguished and intolerable loneliness that frightens him ever more, even though he is never alone in the midst of the smartphonite. Indeed, the time has finally come for us to recognise a fact: we live in a fallible society in which if a flaw is plugged and an imbalance corrected, then another one manifests itself shortly afterwards. Through the smartphonite we must administer the unstable, knowing that it is the most precious asset we possess. Our style, our medial non-definition, proceeds through uncertainty, without referring to the past to find solutions that reveal themselves to be oppressive. What is digital terrorism if not a form of atomised warfare, claiming victims one by one; a conflict maintained through communication? Turning a blind eye, perhaps because of too much light, is tantamount to making the iconic a matter of omertà.

This is the truth of the cross-media citizen who, in dealing with the image as an asset to be distributed, always realises too late, like Polyphemus, that he was dealing with ‘Nobody.' That ‘Nobody’, Odysseus, who made oars wings for a mad flight. Similarly, in reading these Mediangels, there is both a tone and an encounter and only within the character of the painting itself does this voice find its tone; a tone that does not fade. Moreover, in matters of media, the voice cannot predefine the appropriate cause. Not even whilst aiming to grasp the significance in silence. It was therefore a mistake for the citizen orator who, in order to make the best impression whilst declaiming to the crowd, was accompanied by a smartphone that suggested the most appropriate moments to raise his head to the crowd. Does a bowed head allow one to keep step with the truth? Is expression the art of what happens to ‘Nobody’? Indeed, once the painter's gaze has been turned and fixed on the urban scene, and once it has shed the role of scientist and humaniser of the whole, it finds in its narrative and poetic capacity the gateway to a way of recounting the world through the great dilemmas of humanity, such as the screen, chance or the possible ambiguities of everyday life. Pictorial thinking reveals a re-thinking that, by becoming mythical, neither offends nor annihilates the object of thought or the thinker, since, as always, we find that “in the beginning was the fable” but also that “the end is also a fable”. Knowing that one is part of a narrative thread perpetuated through other images on other smartphones, a terrifying realisation in itself, is a guarantee that one is part of the contemporary media gaze.

This is indeed the sitz im leben of myth for Pulze, and of myth in general: to know and yet never fully understand what one is trying to scrutinise. If you study this beautiful collection in one go, you will quickly grasp the very depth of Pulze's stylistic talent and his personal way of imagining and narrating Mediangels. What remains for the attentive reader of these paintings is the pleasure of having witnessed the "incarnation" of myth through the thousand faces of visual technology, which the more it becomes a "fable", the more it lends itself to the viewer, who is called upon never to forget that it is the image that is at the service of the human and almost never the contrary.