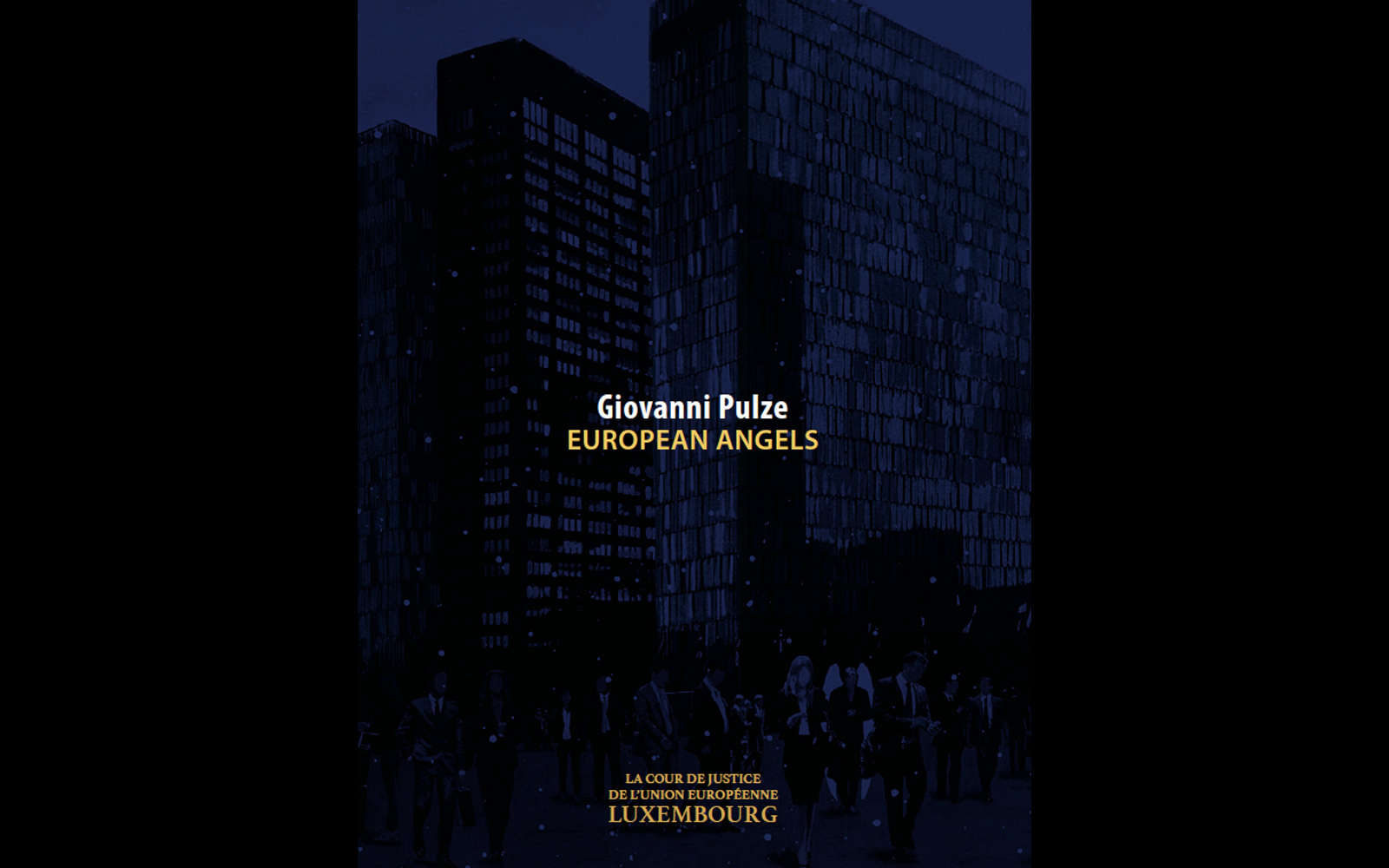

BOOKS / 2022 EUROPEAN ANGELS

THE “POWER” OF “ANGEL”

Giorgio Derossi

When looking at Giovanni Pulze’s paintings, one is immediately struck by a sharp contrast, accentuated dramatically by vibrant and almost provocative colours: that is to say, the contrast between, on the one hand, squares and streets of large over-lit, over-crowded and over-hectic cities, and on the other, the feeble glint of a shadowy, solitary, almost static figure. What is striking is the total non-involvement of this figure as regards the surroundings in which he finds himself, apparently by chance. And it is an impression that becomes even more acute the moment one notices two strange white or grey stump-like projections, similar to wings, protruding from his back – the characteristic mark of an angel, as is also, in the angelology of the aniconic religions, the hiding of the face behind a blank. There is no doubt that it is an angel, humble but not fallen, since by no means does he resemble a fearsome demon.

But to which category of angels does he belong, among the many traceable ones in the multitude of religious traditions? It is certainly not a Seraph, who has six wings: two to cover his face, two his feet, and the remaining pair to fly. Nor is he a Cherub placed, with a flaming sword, guarding the entrance to the Garden of Eden, from which Man was originally banished; nor one of the four or seven “Archangels” or “Angels of the Faces” : Gabriel, Michael, Raphael, Uriel, Raguel, Sariel, Geremiel. It seems clear that Pulze’s Angel does not allow himself to be categorized and that he presents himself as a simple, unidentified, “angel”. Not so much a member of the “Divine court” as in particular – according to the Greek etymology which translates the Jewish – the “Messenger”, the “envoy” who delivers a message, like the emblematic one of the Annunciation: “Angelus Domini qui nuntiavit Mariae”.

But our angel, with his possible message, certainly does not have the splendour that radiates from the description of the Annunciation in the New Testament. The possible “news” of which he is the bearer does not seem “good” but somewhat disquieting, like himself, a “mixture” of characters, more human than divine. He does not appear – as in the main religious traditions – to be a representative of a transcendent “Power”, but rather the contrary, of a “powerlessness”, not being capable of even attracting the attention of the people surrounding him: he appears, but he is not conspicuous; he is, in his colourless apparel, almost invisible. However, it is precisely this iconic mark that constitutes the essence of the angel: he shows us, or rather allows us to glimpse, the invisible within the visible. And this has a peculiar significance, insofar as it unites the represented angel with those who look at the “representation” and with its creator.

There are, in fact, different levels of “observation” of the invisible-visible: there is the observation which perceives a certain “strangeness” in the character which does not, however, differentiate him substantially from the others, apart from his singular appearance; then there is a more thorough observation which can discern a substantial difference, namely the angelic nature of the figure; and finally, a yet more attentive observation can reveal and underline his angelic function. To this last level of observation, one cannot fail to match a corresponding level of “creation” on the part of the artist. What brings the figure of the angel into the “Sacred” context – along with its human creator, namely the artist – is not so much its necessarily divine nature as its function, which is its very raison d’être. The functions are many (to announce, to protect, etc.) and are all manifestations of the divine “Power” (“nomen est officii, non naturae”). Whilst nature distinguishes (even though it does not separate) the divine from the human, the transcendent from the immanent (sky and earth), the functions connect them until they interpenetrate in an almost “sacramental” way.

Representing, or better presenting, this quasi-sacramental merging in the angelic function is, therefore, an act of “creation”, not only artistic but also “religious” insofar as it is the generator of a union which is communion: it is this double significance of the creative act, to transform the figurative “representation” into evocative “presentation”, the “painting” into the “icon”, the “artist” into “prophet” sui generis (namely he who, by painting, becomes a spokesperson and visible announcer of the invisible transcendent Power, of the “totally Other”).

At this deeper level of observation and interpretation it is possible, then, to rescue the angel from anonymity and “baptize” him with the name that seems the most appropriate among the many attributed to him by religious Tradition: namely that of “Angel” (understood not as a common noun but as a proper noun). So, what does this recovered and re-baptized Angel announce? What can be announced by One who has no power, no voice and indeed no face, and nobody – apart from the odd child or stray dog – to look at or listen to him? It is precisely this that he announces: namely, that his total lack of power makes visible the impending meaninglessness, the pervasive inhumanity of present-day human “living”. And he also testifies that it is artistic creation that restores to him the primal power of showing those who observe the painting what they cannot see when observing reality.

By virtue of this “iconic power” of the painting we see the inner void of the people frenetically busy and irresistibly attracted – like robotic mannequins – to the luminous images on which their eyes are glued like agitated moths; we see and realize that they do not care for what is Different because they are not aware, given that it doesn’t shine, shout, or even move. This post-modern Angel, therefore, is not even like John the Baptist, a “voice crying in the wilderness”, that “populous desert” made up of the disconcerting squares and streets of the sprawling metropolis, perpetually clogged and suffocated by hectic traffic.

The new, unprecedented Power that the ancient Archangel did not have, however, lies precisely in this eloquent silence, in this visible invisibility: the Power to show, in the drawings of the Artist as authentic icons, the helplessness of post-modern Humanity, prisoner of a deaf and blind Emptiness into which it is increasingly withdrawing. The apparent insignificance of Angel is therefore nothing more than the image of our insignificance. It is not an image of the Divine, but of a fallen Human: but for this very reason, a “sacred” icon, because it can make us aware of our condition and hence open a passage of hope towards a possible “redemption”. Only by seeing our impotence reflected in his can we, in fact, hope to save ourselves from the Angel of Death which nowadays is upon us like a terrible Demon, already figuratively described in the angelology of the post-Koranic myths.

He is one of the four Archangels and is of cosmic proportions, given that one of his feet rests on a seat of light in the seventh heaven and the other foot is on the bridge between Paradise and Hell. He is seventy thousand feet tall. He has four thousand wings and four faces, and his body is completely covered in eyes and tongues, as many as of those living. During the creation of Adam he managed to tear from the Earth the handful of clay necessary to God for the creation. For this achievement, God entrusted him with the task of Angel of Death – far more terrible than Death itself - because he had created Death first and had invited the angels to look at it, terrified, for thousands of years.

If the rendering of “Angel” does not have the redemptive effect hoped for, this could be the next rendering of another invisible virus, lethal for a Man without soul and future, devoid even of the presence of the merciful Angel who still comes to our aid in the “post-modern icons” of Giovanni Pulze, creator of the “power of Angel”.